The following article is a reworking of my notes for the presentation “Untangling Hellish Visions” at the 2012 IANDS conference; it is not a word-for-word transcription. The original lecture is available as a CD or DVD from iands.org. Copyright 2012, all rights reserved.

Today I want to talk about hell. This will be a very basic level of attention to the subject, and my question today is not, do you believe in hell? My question is, what is it?

We’re in a difficult position these days for talking about hell because of the current tumult about the role of religion. This is a first in human cultural history, because for 4000-to-maybe-10,000 and more years, religion has been the foundation on which people—entire peoples, in fact—built their lives. For those hundreds of human generations, religion has supplied the stories that explain the way the world works: Where did we come from, and where are we going, and why are we here, and what does it all mean?

Right now Western religion and its ancient stories have become suspect in many quarters. After two thousand years, Christendom has moved off center stage, and we don’t know what’s coming to take its place.

We’re between stories. Great sweeps of people are saying, I’m not religious; I’m spiritual. But the thing is, our culture is still lived against a background of the stories of the religions that built the culture. We come to this as Westerners, so I will be talking about hell as it has been described in the Abrahamic sense, specifically in Judeo-Christian traditions. So today I’m saying, never mind whether you believe in that hell or not; as a concept, it is part of the culture. My question is, what is that concept, and if we don’t agree with it, is there an alternative?

Cosmos

In the beginning, or at least the beginning of all the enduring religious traditions, there was no clear sense of what an afterlife might be like. However, as first described by Hindu, Babylonian, Persian, Egyptian, Greek, and Hebrew traditions, one element was essentially shared: the dead had to go someplace. And so, throughout the ancient Near East, the grave became associated with an underworld, the region of the dead. What happened there, if anything did, was left vague; but that underworld was assumed to be simply part of the cosmos, a geographical place, and the idea held for thousands of years. In Hebrew, the region of the dead was called Sheol.

Sheol had no particular religious significance because Yahweh, the Hebrew god, was conceived of as lord of the living, of this world. God’s judgment therefore applied to the here and now, during life, in which good things would happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people; judgment was rendered in life, not after death. And so Sheol served as a warehouse for all the dead, good and bad alike; Moses and the Patriarchs would be there, and all the family members of blessed memory, there “in Abraham’s bosom,” because of course Abraham himself was in Sheol. The sense of Sheol’s being a place of torment after death is never used in the books attributed to Moses or by the early Prophets.

What was religiously important happened in life, when everyone was part of the struggle as a nation to keep its relationship right with God. “Right” was measured not by holding certain beliefs but by living according to holy laws.

Zoroastrianism

About 2,500 years ago, 500 years before the Common Era, in one of a long series of invasions and conquests that tormented the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, the Persian Empire took over and ruled for 200 years. Persian influence brought two new ideas to Israelite thought: dualism and apocalypse.

The Persian religion was Zoriastrianism, which taught that everything in the cosmos is in eternal struggle between opposing sides: good and evil, light and dark, this life and afterlife, Ahura Mazda, the god of light, against a force of wickedness. Matched pairs of good and evil on all sides. Think Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, Harry Potter and Lord Voldemort. Fire was a primary symbol, representing light (the Light) in conflict with darkness; fire indicated the presence of the sacred and purifying. The purifying would come with judgment in an afterlife, and although it would be painful, it would be temporary.

Zarathustra, the founding prophet of Zoroastrianism, seems to have invented the concept of apocalypse—literally, “the making wonderful.”[2] Apocalypse describes how, when human evil becomes too much, divine intervention will bring about the end of this world, followed by a glorious new world. Apocalyptic thinking is fueled by a combination of extreme human suffering and moral conviction. It reflects a kind of subjective desperation, a belief that the world is too chaotic, too wicked and too full of misery to continue existing. The primary requirements for apocalypse are unremitting stress, unfulfilled desire for justice, an expectation of divine intervention to set things right, and vivid imagination.

What Zarathustra taught was that for now, disorder outweighs order and evil outweighs good; but in the final days a savior will come to defeat evil and lead the world into a new age. All suffering, illness, and death will end forever; the dead will come back to life; and everyone who is faithful to the teachings will enter into a Golden Age of bliss. Those who do not agree will be purified in a river of molten metal.

Leaving out that particular river, this should sound oddly familiar. These colorful ideas stuck in Israelite thought, as we can see in their influence across the centuries, and have continued vigorously right up to today.[3]

The Greek Hades

After two centuries of Persian rule came the Greek military genius Alexander, and for the next 200 years the earthy pragmatism of Jewish thought and the dualism and apocalyptic thinking of Zoroastrian religion mixed with the aggressive Greek passion for human reason and art and philosophy, and its multiplicity of gods. The Greek underworld, Hades, was initially almost exactly like Sheol—the words can be used as synonyms—but some of the Greek religions believed strongly in rendering justice through punishing evildoers, and the idea grew that an afterlife in Hades would involve some unpleasantness. However, the atmosphere of Hades was more gloomy than cruel, and punishment was believed to be temporary.

Roman period

Another 200 years, and in 63 BCE the Greeks were overthrown by the Romans. Rome brought military power and emphasis on law and order. But order in that country was an overlay, with unrest just underneath the surface.

At the turn into what we call the Common Era, life was brutal. The eastern Mediterranean had seen a constant history of invasions and war and murderous internal feuding. Some Jewish leaders had crucified and otherwise murdered thousands of their own people, and if they were not putting down local rebellions, the Romans were doing so. Punishment for even minor wrongdoing was harsh and often hideous. Apocalyptic thought was everywhere, with hints of imminent revolution and expectations of the end of the world; tyrannical military occupation existed side by side with guerilla bands of zealots, with rumors of a Messiah coming to overthrow the Roman oppressors. Hell seemed quite plausible. It was easy to imagine that a wrathful god would enact terrible torments after life as a means to justice. Moving the all-too-real cruelties of physical life into an afterlife also gave people a way to think of vengeance, of getting back against all those who made this life intolerable. It was the dark side of justice becoming visible.

In that environment in the year 33 CE, the prophet and mystic Jesus was convicted of treason for complex political and religious reasons. He was crucified as a common criminal by the Roman authorities, and died, but on several occasions later was reportedly seen, living, by his students and followers.

The first surviving writings from any of Jesus’ followers are letters written by the traveling missionary Paul over a period some twenty to thirty years after the crucifixion. Paul clearly expects the risen Christ to return at any moment, bringing an end to Israel’s suffering. He assumes there will be judgment by God but does not mention physical torment or anything we might call hell; the wicked will be quickly destroyed, while non-believers simply die and disappear. Further, in Paul we see how Greek influence has been overtaking Hebrew thought: here, for the first time, what to believe is as important as how to live.

Beginning some forty years after Jesus’ death and continuing until the end of the century came the four accounts about his prophetic career and teachings that we know as the Gospels. Three of them—Mark, Matthew, and Luke—bring the Good News (the meaning of “gospel”) that Jesus is inaugurating the Kingdom of God. John, the last of the four, is more highly spiritualized.

In the tradition of the God-saturated Hebrew prophets, Jesus was a mystic, a visionary of extraordinary personal charisma and power who functioned as both teacher and healer. He healed by touch and at a distance, and by casting out demons. However, they were not quasi-physical demons as we think of them today; the demons he cast out were invisible, the first century’s understanding of mental illness.

Mostly what Jesus taught was that the nation of Israel was to be faithful to the spirit rather than the letter of their Moses-given laws about how to live according to God’s rules, the essence of which is to love God and care for others, both animals and people. Jesus claimed, quite rightly, that Israel as a nation was ignoring justice and the needs of the poor and helpless. If they did not change their ways and their values, he said, if they did not show more care for God and each other, they would be destroyed. In other words, Jesus went up against the power structure of the Jewish hierarchy as well as against Roman oppression. The destruction he anticipated—and which would come all too soon—was that their stubbornness would lead to the obliteration of Jerusalem and the Temple, and a massacre of the Jewish people.

The term Jesus used for this was the metaphor of Gehenna.

GEHENNA

Gehenna (GeHenna) is a narrow valley that runs alongside the old Jerusalem. In that valley, some 900 years before Jesus, King Solomon had permitted the Canaanites to construct a temple to the god Moloch. Moloch was a god of human sacrifice, most specifically child sacrifice, and infants offered to him were roasted alive. The practice was so horrifying to the Jews that the temple was soon destroyed and its location declared an abomination. Known as the Valley of Slaughter, the place was used as a sewer, and later as a burning dump for the worst possible refuse of the region. The bodies of dead animals were thrown there, and those of criminals. It was a loathsome end.

Jesus warned that the nation would suffer torment like being thrown into Gehenna if they did not mend their ways. In fact, that is what happened some forty years later, when Jerusalem and the Second Temple were virtually obliterated by the exasperated Romans, with slaughter and destruction and burning. That was the vision: Gehenna is an image of real-world suffering for Israel, not of suffering after death.

The highly spiritualized Gospel of John never mentions Gehenna or any other version of hell. Throughout the four gospels, although there are individual verses that can be interpreted as warnings, the afterlife judgment and punishment of individuals as interpreted by later theologians were never at the core of Jesus’ teaching.

One other New Testament word that has been interpreted as hell is Tartarus. The reference comes from the Greek myth in which the semi-divine Titans threaten to destroy human beings and Zeus punishes them by locking them in a deep place in Hades, called Tartarus. In the New Testament, the word appears just once, referring to God’s casting fallen angels into Tartarosas. The Greek audience would clearly have understood it as a literary allusion.

The conclusion is unmistakable: hell was never the point of Jesus’ teaching or message. Although a few individual verses can be misinterpreted to give the impression of such a thing, nowhere in Jesus’ teachings is there anything like afterlife hell as it has come to be known. Unfortunately, with the passage of time, cultural forces grew louder than the voice of the messenger.

REVELATION

The closing book of the New Testament is Revelation, the vision of an unknown author named John, the primary source for most of our popular notions of hell. We would be astonished and amused if we thought that people 2,000 years from now could watch one of today’s Batman movies and understand it as something we believe as factual. But that is what we do to Revelation.

Revelation is apocalyptic literature, like the sci fi of its time. It has been described as “John has a nightmare in a cave, in which gentle Jesus is impersonated by a divine sadist.” [4]

When Revelation was written at the end of first century, the scattered groups of Jesus-followers around the Mediterranean had been living with stresses we who live away from war zones can barely imagine. Not only had they endured the madness of Nero (being eaten by dogs or lions, or set aflame as torches), and the bloody, fiery massacre of Jerusalem, but they were living through decades of intense culture clashes. Further, bitter turmoil and hostilities were rampant inside their own ranks, as differing interpretations of Jesus’ teachings emerged and were fought over. Coming from that time, the vision that became Revelation combines a fantasy of vindictiveness with a dream of rescue.

The images and symbols of Revelation are often violent and sometimes vicious, but they are forms of coded religious and political fantasy rather than reality, and its language is cryptic, metaphorical, and highly symbolic. Revelation is not journalism! What it communicated was religious factionalism and political revolt, not literal fact. The problem comes when a literary vision of the first century is read in later centuries as if it were factual news reporting.

There have always been, in Judeo-Christian tradition, two streams, one witnessing to a God of love and the other to a God of wrath. In Revelation, wrath wins, ironically in the name of love. When such a fantasy is concretized, interpreted literally, the concept of a punitive hell takes on more weight. In Revelation we see the beginning of a sadistic strain in Christian theology that would persist to the present time.

As example, there is the Abominable Fancy, the notion that the blessed in heaven will perch, like birds on a branch, over their counterparts in hell and delight to witness God’s justice: “They shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels, and in the presence of the Lamb: And the smoke of their torment shall ascend up forever and ever. Rejoice over her, thou heaven, and ye holy apostles and prophets; for God hath avenged you.”

Doctrine

Within three centuries, differences of interpretation had solidified into contentious camps with lethal consequences. In the year 306 Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, the wedding of religion with political power. Remember the Roman love of law and order: Contention would be contained, turning alternative beliefs into heresies. And into this time of standardization came the great Augustine— simultaneously a brilliant theologian and a tormented psyche. In his work we see how doctrine, grown out of Greek intellectualization and Roman correctness of beliefs, would completely overtake the Way, the Hebrew emphasis on living rather than thinking one’s religion.

The line of sadistic moralism in Christianity did not begin with Augustine, but in him it flourished. Ideas about sin and punishment and hell became inextricably linked with each other and with sex (about which he was seriously conflicted). For Augustine, hell is sensory, a bodily torture that punishes demons and humans alike, and is both physical and never-ending punishment. The bottom line is that because of his power as a theologian, that view became doctrine, which during the next nine hundred years would become elaborated, further institutionalized, and well-nigh universal, leading straight to the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri, known universally simply as Dante!

DANTE

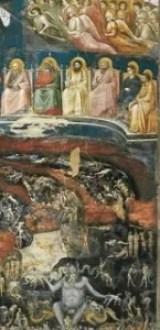

It is hard to overestimate the influence of either Zarathustra with apocalyptic thinking or Dante with the Inferno, his literary masterpiece. Dante’s description of the seven levels of hell, a festival of sins, is a showcase of all the morbid implements of the human imagination—the pornographic, scatological, sadistic elements inherited from persecutions and perversions within the deep psyche, that would be passed on to the Inquisition and other torture chambers. In it we see the very understandable human desire for justice transformed into a pathological vindictiveness, rationalized as vengeance against the Oppressor and sin, now projected as an ambition shared by God.

Between the power of Augustine’s doctrine that hell is eternal, physical punishment without recourse and the vivid imagery of Dante’s Inferno drawn from that perspective, the concept of the medieval hell became ubiquitous throughout Christian nations.

MISTRANSLATION

Despite the strength of belief, that concept of hell, with its accompanying demonic presences and eternal torment is still not biblical. What happened to further the impression of its validity as scripture has been largely a matter of mistranslation, particularly in English Bibles.

Take, for instance, the meanings of three words from the earliest biblical writings in Greek:

- anion – our “eon,” an age, a long time

- theion – probably sulphur, used as incense as a reminder of the presence of God in some rituals (note “theo”)

- bazanizo – to test precious metal for purity

In addition, four place names we have mentioned have been mistranslated:

- Sheol, Hebrew region of the dead, mentioned 65 times in the Bible;

- Hades Greek region of the dead, mentioned 10 times in the New Testament;

- Tartarus, mythical underworld pit, mentioned once as a literary allusion;

- Gehenna, used 12 times by Jesus as a metaphor of physical destruction prophesied for the nation of Israel.

The 16th century translators who produced the King James Version of the Bible believed in the Augustine/Dante, medieval concept of hell. As a result, when they came upon words whose meanings had changed, they overrode what the Bible actually said in Hebrew or Greek with their own interpretation. The meanings of these key words became completely distorted:

- anion, meaning simply a long time, became eternal, everlasting;

- theion, a reminder of God’s presence, became brimstone, indicating the wrath of God;

- bazanizo, to test for purity, is translated as to torment.

In other words, a period of correction has become eternal, the presence of God is understood as wrath, and purification has become torture.

Further, with place names, instead of 75 references to a shadowy place of the dead and twelve metaphoric references to impending destruction, English translations have included almost 90 mentions of “hell” interpreted as a fiery place of eternal torment, which was not intended in the original Hebrew or Greek.

SUMMATION

Although some subjective experiences are terrifying in the extreme, the concept of hell as an actual place has never been a constant and is almost entirely a figment of human imagination. Cultural understandings of hell have changed over time, influenced by human experience and psychology. Punishment is a late development. Grisly tortures seem to follow periods of violence and stress in the world, and are then projected as being a desire of God.

In fact, the idea of a sadistic hell of everlasting physical torment perpetrated by demons and devils has no basis in the Jewish Bible or the teachings of Jesus or Paul. One can validly argue that there is no spiritual authority for that view, although it has persisted for 1,700 years.

The history of Western religious thought moved from the afterlife as an egalitarian region of the dead, through centuries of human suffering at the hands of other people during which we can trace development of an overwhelming desire for vengeance, which was ultimately projected onto God as the divine plan. By misinterpretation and mistranslation people came to believe this is what Western sacred literature says.

And although Dante has been dead for 800 years and the first English translators of the Bible for 500, their vision of hell saturates our culture. We encounter that hell in films and video games, in music, comic books, television, even in a Lego display. Our thinking is so embedded in the concept, there is no alternative in the popular imagination, other than to claim, “I don’t believe in hell.” No wonder people are terrified by a distressing near-death experience!

PROBLEMS AND QUESTIONS

There are substantial problems beyond hell’s being non-scriptural that we don’t have time to deal with here, but which need mentioning. One of these is moral: that this continuing view of hell puts God in violation of the Geneva Conventions about the humane treatment of prisoners. Another is cognitive dissonance: that because we live in a Hubble universe, many of us know too much about geology and astronomy to believe in hell as a tangible place somewhere in the geography of space and time.

Ironically, although disavowing that hell, we cannot say categorically that something like hell does not exist, because these NDEs keep happening.And not only NDEs. There are hellish deathbed visions, and closely related stories of alien abductions, and lucid nightmares, none of them readily explainable except by conventional, literal interpretations.

Something happens: What are these experiences? What do they mean? If we can’t demonstrate hell’s actuality as a place, or as a religious doctrine, what can we know?

We know that something hellish has actuality as experiences in people’s lives.

So let’s look from that perspective. Let’s take our clue from the Jewish way of wholistic thinking and look at these NDEs not as a demonstration of afterlife but in the context of experiences in this life, this world.

A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE

A distressing NDE, especially a hellish one, can be approached not as an afterlife threat or divine punishment but as a mandate to take a new perspective on life and world.

Even blissful NDEs, like other paranormal and numinous experiences, demolish previous certainties. Psychotherapist John Ryan Haule[5] has written of his profound shock at having an out-of-body experience, with a description that will sound familiar to many readers:

Such knowledge disrupts everything I have known…from earliest childhood until now…The world cannot be as I have constructed it; it is unimaginably different. It constitutes the death of everything I have come to know and depend upon. I am not who I thought I was and the world is not as I assembled it. I have entered a realm that is Wholly Other, and I have not the faintest idea what it is or how to negotiate it. I have lost all certainties. Nothing is dependable. Anything can happen. …It is as if we suddenly see a rip in the fabric of the universe.

What these events do is, they dismantle what we think of as normality. Psychiatrist Stanislav Grof has observed many times that the experience of extraordinary perception, which includes events like that out-of-body experience and NDEs, can be associated with deep metaphysical fear because it challenges the Western world view of what constitutes sanity.

Another psychotherapist, also a near-death experiencer, Alex Lukeman has identified[6] the phenomenon as “…the ego’s encounter with the underlying unconscious and transcendent dynamics of the numinous [the Holy], and the accompanying destruction of traditional and habitual patterns of perception and understanding, including religious belief structures and socially accepted concepts of the nature of human existence and behavior.” Wow.

In some traditionally described hellish NDEs, the experience itself may contain features of the classic pattern of shamanic initiation and the most profound spiritual events: the pattern of suffering, death, and resurrection. This may felt as if physical, involving a vivid sense of dismemberment, annihilation, and reconstitution. But always, as explained by the late Jungian John Weir Perry,[7] the cycle of suffering/ death/resurrection is a universal pattern which in less metaphoric terms can be read as an invitation to self-examination, disarrangement of core beliefs, and rebuilding.

In the medieval religious view of hell that we have just traced, the primary assumptions are that hell’s constituents and source originate directly from divine action or indirectly by divine decree, that torment is imposed by an external force, that the precipitant of hell is an individual’s guilt (for culturally disapproved behavior), and that hellishness involves bodily pain.

But what if the view shifts from an external force to internal? What if our approach to understanding these NDEs does not ignore religious influence but considers an individual’s psyche as the source of distress, whether as the avenue through which God works or as a non-theistic mechanism? In Perry’s own words, “Stress may cause highly activated mythic images to erupt from the psyche’s deepest levels in the form of turbulent visionary experience. … comprehension of these visions can turn the visionary experience into a step in growth or into a disorder perhaps as extreme as an acute psychosis.”

Today’s presentation can do no more than point a finger and ask a question. What if, as John Weir Perry claimed, the challenge is “to encounter the death of the familiar self-image and the destruction of the world image to make room for the self regeneration of them both”?

The question brings us back full circle to the religious theme of apocalypse: turmoil, dissolution, the end of an age. Suffering, death, resurrection. Self-examination, collapse of assumptions, rebuilding.

Apocalypse is psyche writ large. And so, despite all the end-of-the-physical-world predictions across the centuries, the macro apocalypse does not arrive. Consider the possibility that the non-arrival is because the prophecy is not about the world but about the self. What changes is the individual psyche, the reconstituted perspective that can say the great “Aha!”

“Oh, now I understand. Ahh, I get it.”

And that, properly understood, might change the world.

References

[1] Carol Zaleski, 1987. Otherworld journeys: Accounts of near-death experience in medieval and modern times.New York:OxfordUniversityPress.

[2] Frances Carey, 1999. The Apocalypse and the Shape of Things to Come. Toronto:University ofToronto Press.

[3] John Michael Greer, 2011. Apocalypse Not: Everything You Know about 2012, Nostradamus and the Rapture is Wrong. Berkeley,CA: Viva Editions

[4] R.F.Dietrich. “A History & Criticism of ‘The Apocalypse’”, at Rennes-le-Château website, http://chuma.cas.usf.edu/~dietrich/apocalypse.html

[5] John Ryan Haule, 1999. Perils of the soul: Ancient wisdom and the new age.York Beach,Maine: Weiser.

[6] Alex Lukeman, 1998. Book review of Edward F. Edinger, Encounter with the self. Retrieved from. Tiger’s Nest Review. Created 3/25/98; accessed 9/4/01. http://www.frii.com/~tigrnest/encount.htm.

[7] John Weir Perry, 1998. Trials of the Visionary Mind. Albany,NY: SUNY Press.