Happy New Year wishes to you all, and here we are, back again with Dancing Past the Dark. The long hiatus in posting resulted from my sense of having reached my limit with the original 100-some posts; in other words, I didn’t know what more to say.

I had not expected the persistence of some readers who declined to just walk away. They, plus the report of a new study out of the UK, have effected this reappearance; so let’s get to it!

* * * [Read more…] about Advanced Meditation and NDEs

Religious issues

What about religion and distressing NDEs?

Part 1 of 3

The subject of this post results from a small crowd of blog comments and emails following the posts about my conference presentation,“Untangling Hellish Visions,” and the documentary Hellbound? For example, here are quotes from two typical comments:

- It’s terrifying that such a god might exist and is actually believed to exist by millions and millions of people. I agree with the other poster who said they pray that religion isn’t real: such a possibility is a nightmare.

- I don’t know what to believe any more, and I am so afraid. What is wrong with religion?

The June, 2012 issue of Nature magazine carried an interesting report about the closeness of our genetic relationship with apes. Scientists have known for several years that we share almost 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees, our closest relatives. Now bonobos, the chimps’ sibling species, have joined them in our DNA pool. It seems we share 98.7% of the DNA of both species.

Reading further on the topic, what I find most fascinating is the behavioral complexity of this news. Chimpanzees are known to be aggressive, hostile toward strangers, power-hungry, often violent to the point of murderous. Male dominated, they form attack gangs to roam their territory looking for outsiders to fight and kill; a male will kill unprotected infant chimps not his own.

Bonobos, the siblings from the opposite side of theCongo River, are the only peaceful ape. They are reported to be cooperative, curious rather than hostile toward outsiders, and alpha-female-dominated. Unlike chimps, bonobos share easily, even sharing food with strangers; they do not patrol the borders of their territory or practice infanticide.

It is not that bonobos do not experience conflict; they do. However, saysDuke University researcher Brian Hare, bonobos will bite, but they won’t kill. Primatologists say they are hyper-sexual, preferring to “make love not war” as a way of resolving conflicts. Whereas chimps tend to address conflict with violence, bonobos of both genders prefer to settle scores with (non-procreative, sometimes homosexual) sex. Journalist Andrew Sullivan reports about one laboratory experiment that “at times the chimps were too busy fighting each other to complete tasks. But the sexually hyper-promiscuous bonobos could focus…” How very intriguing. [Read more…] about What about religion and distressing NDEs?

Two Families of God, continued, and an NDE ball is thrown out to readers

Those of you with memories that go a couple of posts back may recall that I had embarked on a discussion of what William James called the “healthy minded” and “sick soul” approaches to religion and life. My blog post was based on an article by experimental psychologist Richard Beck, “The Two Families of God,” and I confidently promised to come back and lay out my own views on the subject.

James, you remember, described healthy-mindedness as producing happiness that rests on an optimistic ignoring of evil and the dark side of existence.” The approach, James said, manifests a “blindness and insensibility to opposing facts given as its instinctive weapon for self-protection against disturbance.” In Beck’s words, “This protection is accomplished through repression and denial. It is an intentional form of blindness in the face of life to produce positive affect and existential equanimity.”

In other words, the sunny, happy results of healthy mindedness depend on denial of evil and suffering.

By contrast, what James called “sick souls” remain existentially aware, individuals “who cannot so swiftly throw off the burden of the consciousness of evil…and are fated to suffer from its presence.” As Beck puts it, “James describes the sick soul as more profound than healthy-mindedness; the sick soul experience is ‘a more complicated key’ to the meaning of pain, fear and human helplessness.”

James said of the existential resiliency of the two types:

“The method of averting one’s attention from evil, and living simply in the light of good is splendid as long as it will work. . . . But it breaks down impotently as soon as melancholy comes; as even though one be quite free from melancholy one’s self, there is no doubt that healthy-mindedness is inadequate as a philosophical doctrine, because the evil facts which it refuses positively to account for are a genuine portion of reality; and they may after all be the best key to life’s significance, and possibly the only openers of our eyes to the deepest levels of truth.”

It will probably come as no surprise that what struck me so sharply about Beck’s article is the apparent similarity of James’s healthy-mindedness to the principles of the Law of Attraction, which has overflowed its original New Thought banks, spilled into Norman Vincent Peale’s “Power of Positive Thinking” and Joel Osteen’s Prosperity Gospel, to become an immensely popular new parallel to contemporary religion.

And that is where I—or more specifically this blog post–got bogged down. The more I have tried to analyze the response of Law of Attraction thinking to distressing near-death experiences, the more difficult I have found it to talk about it all coherently. Maybe I’m simply too close to the subject. Maybe I’m just bored by the ideology.

I am certainly aware of the aura of disapproval and fear, along with a kind of moral condescension, projected by Law of Attraction followers toward the whole subject of these types of experience and the people who report them. Ironically, I do not for a moment deny the utility of much LoA psychology nor the possibility that some of its scientific claims are plausible. (I have in fact bent a couple of spoons without physical force; I have a cellular memory of that “action at a distance.”)

What bogs me down is akin to theologian Walter Brueggemann’s claim that “we have thought that acknowledgement of negativity was somehow an act of unfaith.” It is the same model, says Beck, “that creates the sense that James’s sick soul or the experience of Mother Teresa is paradoxical. In the bipolar model, faith and complaint exist at the expense of the other. They cannot occupy the same experiential space. However, as we have seen in the psalms and in the empirical psychological literature regarding relationship with God, it appears that high complaint can coexist with faith.”

Similarly, I contend, acceptance of the existential burden of recognizing the dark side of existence, whether physical or spiritual, is not necessarily negativity as the Law of Attraction would have it. It can coexist with joy and success, and with a deep spirituality.

So, I am throwing this discussion out to you all. You’ve had some great comments about the former post. Do you think distressing NDEs can be accommodated within Law of Attraction thought? What are your thoughts about LoA thinking and human suffering on a global scale? (But please do not tell me that very young children attract their leukemias and blastomas to themselves, nor that the millions of individuals who died in the Holocaust invited the experience; that would be ideology talking, not common sense.) Is LoA simply a different kind of fundamentalism, brooking no disagreement?

The Two Families of God and Near-Death Experience

I’ve been wanting to do a follow-up here on some earlier discussion about attitudes and their relationship with distressing NDEs, so I jumped when the ideal opening came along a few days ago. Today’s post, which introduces our reopened discussion, comes from one of my favorite blog authors, with help from William James and Sigmund Freud. My comments will come along next week, and I’ll be looking forward to yours both now and then. (And as usual, if you don’t care for God-talk, just plunge in anyway; this time it’s only in the title, because William James put it there.)

Richard Beck, PhD is an experimental psychologist, author of two books, the mind behind the surprising and enlightening blog Experimental Theology, and in his day job chair of the Psychology Department of Abilene Christian University. He is emphatically not what most people expect. What follows is reposted here with his gracious permission.

The Two Families of God

by Richard BeckIf you are a regular reader you know I’m a huge fan of the American psychologist and philosopher William James. In fact, James’s most famous work–The Varieties of Religious Experience–plays a key role in my most recent book, The Authenticity of Faith.

The part of The Varieties that captivated me so many years ago is James’s descriptions of what he calls “the two families of God”–two distinct religious experiences James called the “healthy-minded” and “sick soul” experiences.

James begins his analysis in The Varieties with the healthy-minded experience. According to James the healthy-minded believer is positive and optimistic, willfully even intentionally so. The healthy-minded believer actively ignores or represses experiences that are morbid, dark or disturbing. As James describes it: “[W]e give the name of healthy-mindedness to the tendency which looks on all things and sees that they are good.”

James goes on to distinguish between two different origins of healthy-mindedness. The first is a dispositional, trait-like healthy-mindedness, an optimism and positive affectivity that is rooted in a person’s innate psychological wiring–the sort of congenial good-cheer many people seem to have. By contrast, there is also a more decisional sort of healthy-mindedness, an active choice to see the world as good where, according to James, a person “deliberately excludes evil from [the] field of vision.” This isn’t as easy as it sounds. As James notes, an extreme healthy-minded stance may be “a difficult feat to perform for one who is intellectually sincere with himself and honest about facts.”

Why, then, do people indulge in this experience? According to James, people might opt for healthy-mindedness because it is an “instinctive weapon for self-protection against disturbance.” James summarizes how this works:

[Healthy-minded] religion directs [the believer] to settle his scores with the more evil aspects of the universe by systematically declining to lay them to heart or make much of them, by ignoring them in his reflective calculations, or even, on occasion, by denying outright that they exist.

According to James this tendency toward “deliberately minimizing evil” can become almost delusional where “in some individuals optimism can become quasi-pathological.” James suggests that healthy-mindedness can appear to be “a kind of congenital anesthesia.”

In contrast to the experience of healthy-mindedness James goes on in The Varieties to describe the second of the “two families of God”–the experience of the sick soul.

If the healthy-minded experience is typified by a “blindness” that seeks to minimize evil, the sick soul is a religious type involved in “maximizing evil.” According to James, the sick soul is driven “by the persuasion that the evil aspects of our life are of its very essence, and that the world’s meaning most comes home to us when we lay them most to heart.” Sick souls are those “who cannot so swiftly throw off the burden of the consciousness of evil.” Consequently, sick souls are “fated to suffer from [evil’s] presence.”

Of great interest to me in The Authenticity of Faith, James describes the sick soul as being very preoccupied with death awareness. According to James the sick soul lives with a regular awareness of death, that at the “back of everything is the great spectre of universal death, the all encompassing blackness.” In light of this death awareness the sick soul knows that “all natural happiness thus seems infected with a contradiction” because “the breath of the sepulcher surrounds it.”

For James, this death awareness seems to be a key difference between the healthy-minded and the sick soul:

Let sanguine healthy-mindedness do its best with its strange power of living in the moment and ignoring and forgetting, still the evil background is really there to be thought of, and the skull will grin in at the banquet.

The sick soul does not seem to be engaged in a denial of death, to use Ernest Becker’s phrase. And because of this, despite the apparent “sickness” of the sick soul, James suggests that the experience of the sick soul provides a “profounder view” of life. More, the sick soul confers a degree of resiliency in the face of tragedy, setback and pain. Critical to the argument I make in The Authenticity of Faith is James’s summary assessment comparing the two types:

The method of averting one’s attention from evil, and living simply in the light of good is splendid as long as it will work…But it breaks down impotently as soon as melancholy comes; and even though one be quite free from melancholy one’s self, there is no doubt that healthy-mindedness is inadequate as a philosophical doctrine, because the evil facts which it refuses positively to account for are a genuine portion of reality; and they may after all be the best key to life’s significance, and possibly the only openers of our eyes to the deepest levels of truth.

The Buddha in hell

One right after another, three emails recently arrived at my desk with more or less breathless news of a Buddhist monk whose near-death experience account described his seeing the Buddha in hell. It was Big News on the Internet.

Really! The Buddha in hell! Some letter writers wonder, this must prove that the God of Wrath is real, right? And it proves that Christians are right, right? Well… I looked up the account on Google, and sure enough, it’s an interesting story, though the account goes back quite a few years.

http://www.raised-from-the-dead.org.uk/accounts/a/ap-shinthaw-paulu-s1-all.php

Is it convincing? To my mind, no. Excited Internet commenters notwithstanding, the account sounds patently fake, which makes it a useful example to explore.

If you have read the account, you know that the monk presents a thoroughly believable autobiographical background, how he was raised in Myanmar (Burma) and came to be living as a monk. It sounds entirely authentic, even down to details like the sea crocodile that destroyed his boat. (I looked it up—and yes, there are such crocodiles in that area, and that is the kind of behavior one would expect of them.)

The account describes his entering training, and deep respect for his teacher, “the most famous Buddhist monk in all of Myanmar.” It details how he lived for some years devoted to his spiritual practice and to the principles of Buddhism, so scrupulous that he refused even to harm a mosquito that might infect him with malaria, which turned out to be the disease that nearly killed him. Actually, he reports that he had both malaria and yellow fever and grew weaker and weaker.

So far, so good. It’s clear and it’s credible. But now, to my mind, come the problems. They illustrate why readers of near-death experience accounts need to exercise the same discernment they use, one hopes, when receiving an email from Nigeria asking for money. Just because an NDE account says something happened doesn’t mean it’s literally true!

The monk says, “I learned later that I actually died for three days. My body decayed and stunk of death, and my heart stopped beating.”

[Enter Question #1. The “awakened while putrefying” aspect is an imaginative detail but physiologically too much to credit. A genuinely decaying body does not reanimate.]

And then comes his NDE. According to the account, he encountered “a terrible, terrible lake of fire. In Buddhism we do not have a concept of a place like this.”

[Question #2. Lakes of fire are not uncommon in mystical experiences, and Buddhism does include some kinds of hell (Narakas) featuring fiery torments. Wouldn’t a monk know that?]

“At first I was confused and didn’t know it was hell until I saw Yama, king of hell. Trembling, I asked him his name. He replied, ‘I am the king of hell, the Destroyer.’ The king of hell told me to look into the lake of fire. I looked and I saw the saffron colored robes that Buddhist monks wear…”

[Question #4. Yama has an unmistakable appearance; why did the monk have to ask who he was? Yama is a deity, not a king. Why would the famous teacher’s robe not be incinerated in all that fire?]

The monk recognized his greatly revered spiritual teacher and protested his being there. Yama responded, “Yes, he was a good teacher but he did not believe in Jesus Christ. That’s why he is in hell.”

[Question #5. Warning lights and sirens: Yama is a Hindu and Buddhist deity. Houston, we have a problem.

Then the monk saw Gautama, the Buddha, in the fire, and asked, “Gautama had good ethnics and good moral character, why is he suffering in this lake of fire?” The king of hell answered me, “It doesn’t matter how good he was. He is in this place because he did not believe in the Eternal God.”

[Question #6. Yama, the Buddhist deity, would also not believe in the Eternal God. Why is he saying these things?]

The Buddha is followed by a Burmese ruler who persecuted Christians, and Goliath, from the Old Testament, who was a hero but blasphemed the Eternal God. There is more to the account, in scenes from biblical stories and an encounter with St. Peter, all in the same vein.

Question #7: NDEs as a category promote compassion and knowledge but not the doctrines of a specific religion. How is it that every incident in this entire account reflects a particularly flavored view of Christian teaching?

It is altogether conceivable that the essence of this account lies in a genuine Burmese NDE. It is quite true that people typically identify religious beings in NDEs according to whatever labels pre-exist in their minds. Thus it is not unusual for a Buddhist monk to say, “I met Yama.” However, NDEs are not carriers of specifically religious dogmas. What is downright bizarre is that the Buddhist deity would be proclaiming Christian doctrine!

That is why I am convinced that one of two things is true:

- The account is a flat-out Christian testimonial that has been faked as a Buddhist near-death experience, or

- The account began with an actual Burmese near-death experience; but the hand of a Christian evangelical interpreter lies heavily on top of that NDE.

The narrator had lived for a while in Yangon City (Rangoon), which has a far larger Christian population than other parts of Myanmar, so it is likely that he had heard some Christian teachings. Given the missionary influences in that part of the world, those teachings probably included vivid, revivalist descriptions of hell and judgmental torment—the kind that people remember because they’re so frightening. It is easy to see how that could have influenced the NDE of a credulous hearer. It could even be possible that the monk was moving from his Buddhist beliefs to becoming Christian. In any case, one need only add some later Christian embellishments to come up with the account presented here.

There are too many other questions about this account. A genuinely committed Buddhist, particularly a monk, would surely have to wrestle with the content of that experience for more than two seconds before declaring himself a permanent Christian. (Even Saint Paul withdrew for a time after his epiphany before beginning to teach.) We are told that the monk himself went on to convert “hundreds of other monks” and to travel around and testify to his new-found conservative Christian faith; yet he has conveniently disappeared from public view, so can’t be questioned.

Overall, I find this account, as described, beyond credibility as an accurate original presentation of any NDE, much less one of a committed Buddhist monk.

Two things I believe are really important when trying to understand what any spiritual experience means:

1) Like dreams, visionary experiences carry their messages in symbol, not in the literal, fact-filled terms of everyday speech. Taking them at their literal appearance is rarely accurate.

2) In much the same way, near-death experiences seem universally directed to the human spirit and psychology generally, not to the interests of particular religious views. Within the NDE their elements exist principally as images rather than as doctrinal messages, because interpretation comes when the NDE is turned into language and told as a story.

I am respectful of cross-cultural content because I am an observant Christian whose NDE message was delivered by a totally unfamiliar Chinese Yin/Yang symbol. But the presence of that symbol in my experience was not to say that Buddhism is right and Christianity wrong. It took a very long time for me to understand that it was not delivering an explicit teaching about religious doctrine but was functioning as a symbol—like an arrow pointing beyond itself.

Culturally, we see fire in an experience like the monk’s and immediately think “punishment in eternal torment.” We don’t stop to consider that the presence of God has traditionally been associated with fire, as with Moses and the burning bush. In fact, the Bible includes some ninety references to the presence of God as fire. We can do the same double-check with any element of a spiritual experience—what might this mean, other than what seems to be sitting right on the surface?

Certainly we can look at these troubling experience accounts and choose to interpret them as pointing to a traditional, literal hell. But that is our choice. We can also choose to take the time and trouble to explore what else they might mean, what they may be pointing to about our lives or our way of thinking that could use some change, or that would revolutionize our approach to life itself.

It is clear that some spiritual experiences are really scary. Having worked my way through one, I know just how cataclysmic they can feel. But am I ready, after all these years, to say they point to a concept like eternal physical torment? Not on your life. Or mine, either.

The same universe that has room for these profoundly traumatic events also encloses the peaceful experiences that people describe as heaven. It is worth taking time to look at displays of the Hubble photos showing “what’s out there”—wonderful, serene visions of breathtaking light along with black holes and incomprehensible violence. Why should our spiritual landscape be different than that of our universe? We are required to learn how to be with it all, in ways that make sense to us.

The idea that a God of such immensity would display soul-killing wrath because, as one letter-writer wonderfully put it, two early people “ate fruit and had opinions”…that is so incongruent a notion that it makes no sense to me whatever. (Yet there are great truths buried in the Genesis story!) So, let me openly state my conviction that the expectation of such divine punishment as the monk’s account claims is the product, not of God, but of our projection of human fear, guilt, and rage onto whatever we conceive as Divinity. Our doing, not deity’s!

Similarly, I have come to see that the NDE which at first seemed to destroy my faith has turned out to be a gift. Yes, it is a dubious gift but a genuine one nonetheless, because it has required me to examine these kinds of questions. It has forced me to understandings I could not have had otherwise. Howard Storm’s agonizing shamanic initiation experience stripped him painfully of one existence and exchanged it for one more satisfying. Who’s to say that was punishment?

Is the universe friendly?

I’ve been promising to respond with my own answer to Einstein’s question: Is the universe friendly? Needless to say, it’s one thing to pose the question rhetorically and quite another to be expected to answer it oneself, which helps account for the time it has taken to get here.

My answer is tied up in two cosmologies. First, there is the cosmology that has marked the thinking of Western civilization for some four thousand years. The second is the cosmology of today, the Hubble version. First, the ancient Near Eastern view; we still tend to think this way, especially those who are linked to Western religious literature.

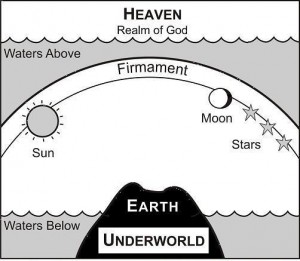

I think of this cosmos as a snow globe. It sits at the very center of a large crystal globe that marks the extent of the universe (beyond the border of the square picture here.)

Think of the rounded snow globe cover as the firmament–made of insulating glass, perhaps, with a space between–a hollow shell holding the winds, snow, rain and hail, with places for the sun, moon, and planets; the inner side of the shell was conveniently fitted with windows through which God and the angels could look down at the earth and its inhabitants. In some conceptions, there were doors at the east and west through which the sun and moon could appear and disappear.

The Great World Ocean surrounded the Earth, as anyone who walked to the edge of land could tell. The great water surrounded the entire globe and was the source of rain and floods (“the fountains also of the deep and the windows of heaven,” Genesis 8:2).

Below the firmament was the earthly sky, shaped like a dome, as the eye can plainly see, and then Earth, a flat disk surrounded on all sides by the great WorldOcean. Below the Earth were the regions of the dead, and, in some views, a fiery place. And below them all were the great waters of the deep, and gigantic pillars, like bridge casings, that supported the firmament.

Above it all, the high heavens were home to God and his light-beings, the archangels, seraphim, angels and cherubim. It was a cosmos that made such sense! It was orderly and understandable. It was secure. Though there were known to be antagonistic Powers, they could for the most part be contained. God had deliberately created Earth to be the center of the universe, and human beings were the very purpose of that Creation, each individual with a secure niche of status and function. Was it a friendly universe? It was at least built to human scale.

You know what’s coming. And if you’ve read the book, you know my take on it. After thousands of years, the sixteenth century BCE began a ferment of astronomical discovery and technological advancement that has brought the twenty-first century to a thoroughly lopsided set of understandings. On the one hand sits the Old Home Cosmos, like the friendly little farmhouse now crowded in by shopping malls, highways, and industry.

Right next to it sit the results of a few hundred years of revolutionary discovery, the conclusion of philosophers of science that we inhabit a mechanistic cosmos with a seemingly meaningless history, and that what we took to be deep-rooted faith in a sacred reality has been nothing but wishful thinking. And the home place itself is merely a flying ember, the coincidental cinder of a great explosion that happened so long ago as to be unimaginable. We live in a Hubble universe.

That we are schizy with our cosmology is evident in a really interesting blog post in which cosmologist Lawrence M. Kraus of Arizona State University says, in part:

“The central problem with the notion of creation is that it appears to require some externality, something outside of the system itself to pre-exist, in order to create the conditions necessary for the system to come into being.

“This is usually where the notion of God — some external agency existing separate from space, time, and indeed from physical reality itself — comes in, because the buck seems to be required to stop somewhere.

“To simply argue that God can do what nature cannot is to argue that supernatural potential for existence is somehow different from regular natural potential for existence. But this seems an arbitrary semantic distinction designed by those who have decided in advance that the supernatural must exist so they define their philosophical ideas to exclude anything but the possibility of a god.

“To posit a god who could resolve this conundrum often is claimed to require that God exists outside the universe and is either timeless or eternal.

“Our modern understanding of the universe provides another, and I would argue far more physical solution to this problem, however, which has some of the same features of an external creator — and moreover is logically more consistent.

“I refer here to the multiverse. The possibility that our universe is one of a large, even possibly infinite set of distinct and causally separated universes, in each of which any number of fundamental aspects of physical reality may be different, opens up a vast new possibility for understanding our existence…

“The universe is far stranger and far richer — more wondrously strange — than our meagre human imaginations can anticipate. Modern cosmology has driven us to consider ideas that could not even have been formulated a century ago. The great discoveries of the 20th and 21st centuries have not only changed the world in which we operate, they have revolutionised our understanding of the world – or worlds – that exist, or may exist, just under our noses: the reality that lies hidden until we are brave enough to search for it.

“This is why philosophy and theology are ultimately incapable of addressing by themselves the truly fundamental questions that perplex us about our existence. Until we open our eyes and let nature call the shots, we are bound to wallow in myopia.” http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2012/04/23/3481105.htm

To each his own myopia. Can such a universe be considered friendly? It is an irony that Einstein, the most famous scientist of the 20th century, is credited with asking the question, for it is one that science is not designed to answer. It is the business of science to deal with quantity, not quality. As Huston Smith puts it in Forgotten Truth: “A number is a number, and number is the language of science. Objects can be larger or smaller, forces can be stronger or weaker, durations can be longer or shorter, these all being numerically reckonable. But to speak of anything in science as having a different ontological status—as being better, say, or more real—is to speak nonsense.”

In short, science cannot provide a friendly universe; it can provide only a description of what it observes physically: the planet Earth as a spinning bit of rubble toward the edge of a nondescript galaxy within a seemingly impersonal immensity. When Einstein asked, “Is the universe friendly?” the answer, according to materialism, has been a resounding, No!

However, the universe is no more friendly, nor any less, than it was before the Copernican revolution began all the fuss. There is as much reason to fear, or not to fear, as in the millenia before. What we know that is different is a matter of scale, of enormity beyond comprehension, of a God, for those who believe in an underlying purposefulness, dealing with significantly more than the Creation on the scale depicted in Genesis.

And despite the necessary mathematical restrictions of scientific method, the residents of this particular bit of rubble are curiously designed to hunger after meaning and purpose. To the everlasting delight of those who are willing to notice such things, it seems that messages keep coming.

Into the universe of clockwork mechanistics, within the lifetime of most of you reading this, came word of yet another mystery. For the first time in centuries, there was abundant suggestion of something meaningful beyond the sterile materialist model. At last, there were people whose direct experience with that “something more” led them to proclaim that, yes, the universe is friendly—not only friendly but loving and welcoming, and it is safe to die. It was no wonder that near-death experiences were greeted like food after famine.

Look at the Hubble photos–the Pillars of Creation, the great sweep of stars looking like an angel’s wing that reminds us just how vast an enormity is, the spirals and spirals of galaxies crowding time and space through billions of light years. We feel the fear of the mortal and insignificant, what ancients sensibly called the fear of the Lord. It is all so vast, of course we are afraid! But then, the great poet Rainier Marie Rilke observed, “Every angel is terrifying.”

Creation has broken out of the gate and is running loose way beyond our little world. So how are we to live in this universe that is both glorious and terrifying, both infinitesimally small and unimaginably limitless? I think we need to recognize that in the face of such enormity, human reason is provincial at best. It may even be absurd, though poignantly so. We try to tame Creation with reasoned theories, with systems of beliefs and ideologies and doctrines like those of science and religion, systems that create mini-universes of those who are “in” and those who are “out.” But we need to remind ourselves that we are the minds and voices of Dr. Seuss’s Whoville. This is not a God to be made captive to our understandings, nor a nature to be tamed.

What I have come to believe is that, as those before us walked in their snow globe, we are called to walk in trust of this mysterious and terrifying universe. I find that I scale it to my tiny level with the lovely NDEs in mind: Just as the Hubble universe is a swirl of glory and terror, brilliance and cthonic darkness, so are our psyches. Remember, we are all stardust.

I listen to the ancient liturgy with Hubble ears. The magic is not in the details of reasoned systems, I think, nor of sanctioned images or accepted beliefs, but in our simple trust.